MYCOBACTERIUM TUBERCULOSIS HOST-PATHOGEN INTERFACE

We are interested in the interface between intracellular bacterial pathogens and the hosts they infect. In particular, we study the notorious human pathogen, Mycbacterium tuberculosis, which remains a major global health threat. M. tuberculosis has evolved a variety of specific adaptations to not only survive but also replicate within the harsh environment inside a macrophage. We want to understand the mechanisms by which M. tuberculosis is able to modulate the innate immune response to establish an infection as well as how the host detects and responds to M. tuberculosis.

How is Mtb sensed within a macrophage?

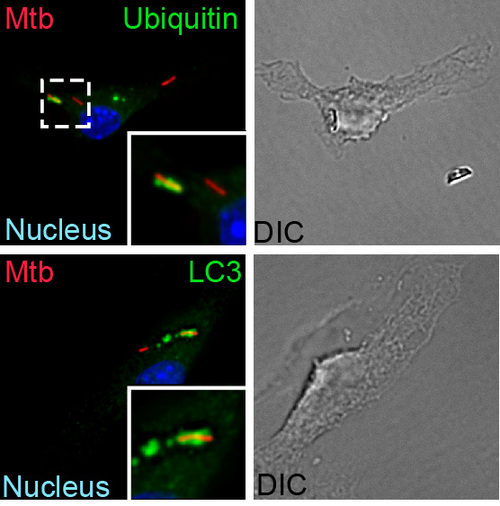

A fundamental way in which the innate immune system discriminates between pathogens and nonpathogens is by sensing membrane perturbations mediated by bacterial virulence factors. This can be achieved by directly sensing damage or by recognizing specific bacterial molecules in the cytosol. We have demonstrated that upon infection, M. tuberculosis gains access to the macrophage cytosol by perturbing the phagosomal membrane via the Sec-independent ESX-1 secretion system. This specialized organelle mediates the transport of gene products, termed effectors, from inside the bacterium across the host cell membrane to modulate host cell processes in order to benefit the pathogen and promote infection. Phagosomal permeablization presumably enables cytosolic access to ESX-1 effector proteins, allowing them to exert their function. This process also permits host signaling molecules direct access to the bacterium and a variety of bacterial components, such as extracellular bacterial DNA, which is a key “danger” signal recognized by the macrophage. After a recognition event that involves the signaling molecules STING and TBK1, the cytosolically exposed M. tuberculosisis tagged with ubiquitin and targeted to the selective autophagy pathway. Importantly, autophagy is essential to control M. tuberculosisreplication both in macrophages and in an animal model of infection. Our work has shown that the type I interferon-producing cytosolic surveillence pathway (CSP) is also induced by extracellular bacterial DNA and also requires the common signaling components, STING and TBK1. Intriguingly, despite sharing these factors, stimulation of each pathway during M. tuberculosis infection leads to very different outcomes: autophagy limits bacterial replication, while induction of the CSP enhances bacterial loads in vivo. We plan to identify and characterize components up and downstream of STING and TBK1 to determine shared and unique components of the selective autophagy and CSP pathway to better understand how these pathways function together during M. tuberculosis infection.

How do individual bacterial effector proteins contribute to Mtb infection?

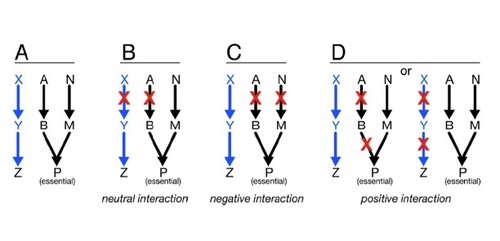

ys using unbiased genetic and protein-protein interaction profiling. To this end, we plan to express each M. tuberculosis ESX-1 substrate, as well as effectors from other pathogenic bacterial secretion systems, in yeast deletion libraries in order to systematically assess how these effectors function to modulate conserved cellular pathways in eukaryotic cells.

ys using unbiased genetic and protein-protein interaction profiling. To this end, we plan to express each M. tuberculosis ESX-1 substrate, as well as effectors from other pathogenic bacterial secretion systems, in yeast deletion libraries in order to systematically assess how these effectors function to modulate conserved cellular pathways in eukaryotic cells.Does Mtb regulate macrophage gene expression post-transcriptionally?

Innate immune cells are able to discriminate pathogens from non-pathogens at the earliest stages of infection and tailor their responses to match the level of threat. Upon infection with a pathogen such as M. tuberculosis, bacterial components are detected either in the vacuole or the cytosol, and a complete reprogramming of gene expression occurs to promote destruction of the bacterium. However, M. tuberculosis deploys virulence factors that modulate the expression of macrophage gene products, allowing the bacterium to subvert the innate immune system and establish a replicative niche. We are interested in studying the precise spatial-temporal gene regulation in macrophages early during M. tuberculosis infection. Specifically, we want to understand how changes in gene expression upon infection are regulated post-transcriptionally (i.e. at the level of pre-mRNA splicing, mRNA release from chromatin, or mRNA export). Importantly, we want to explore whether M. tuberculosis has evolved the ability to hijack normal post-transcriptional RNA processing events via ESX-1 effectors or other specific gene products, in order to promote its survival within the macrophage.